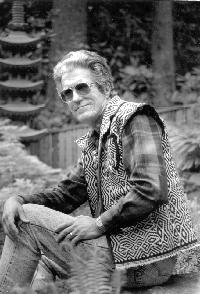

Dr. Drake's Bio

Korean War Veteran - 326th CRC 1952 - 1953

Coordinator, Korean War Children's Memorial

What motivates a guy to spend thousands of hours

of volunteer labor and his own money to develop a national memorial

for a cause that most people are totally unaware of? I'm not really

sure. Let me see if I can figure this out for myself.

About 15 years ago I was sitting next to Paull Shin

at a banquet in Seattle for a high ranking Chinese official hosted by

the Governor of the State of Washington. While waiting for the

meal to be served Paull was telling of his life on the streets of Seoul

during the war as a war orphan. He stopped and looked at me and

asked, "What's the matter?" Tears were streaming down

my face. The "matter" was that his words took me back

to my days in Korea where I spent a lot of time trying to help the orphans.

His words unleashed emotions that I had buried for many years.

A neighbor of mine who served with a MASH unit in

Viet Nam recently commented that perhaps the American GIs spent so much

energy to help the children of Korea during the war as a way to assure

themselves that they were good, decent, upright American human beings

and not killers. War is hell. War is the antithesis of all

one is taught in the family, in the home, in school, in the community.

War is death and destruction imposed on other human beings. Our

soldiers had to be taught to point a gun at another human and shoot.

They did not have to be taught to pick up a crying child and comfort

him or share a bit of food with a little waif begging at the gate to

the army camp.

I hated Korea. I hated the destruction, the

loss of life, the debasement of human values. I hated the smells,

the abject poverty all about, the last bodies not yet picked up and

buried from battles fought weeks or months ago, the mined fields you

had better not enter for fear of being killed. And I hated the miserable

winter cold. A tour of duty in Korea during the war period was

not a pleasant experience. I was not in a combat unit but rather

was assigned to the 326th Communications Reconnaissance

Company which was an Army Security Agency radio intelligence company

located a fairly safe distance from the front lines.

I was one of the few

fellows in our operations unit that had no college education but I did

have a lot of experiences that they did not. When I was but 15

years old I put a knapsack on my back and took off on a three-month

hitchhike trip around the U.S. and Canada. Later, when I

finished high school, I bought a bicycle and with a hundred and eighty

dollars and a letter of introduction from the Boy Scouts of America,

I took off for South America aprendiendo mi espanol en las calles, cantinas

y pulquerias (learning my Spanish in the streets, bars and gin mills)

of all the countries from Mexico to Panama. I ended up in Panama

with 13 dollars and no bike. In order to replenish my funds I took a

job with the Inter-American Geodetic Survey as an engineer aide.

It was a wonderful experience working deep in the jungles and on mountain

tops throughout Panama and, later, Guatemala. By June of 1950

I had saved enough money to return to the 'States to begin college but

when I arrived in the U.S. the Korean War had begun.

It looked like college

would not be in the works so, before the draft board called, I took

off for a six-month hitchhike trip throughout Europe. Then I came

home and enlisted in the army. I sought assignment with the Army

Engineers but was soon sent to school to become a high-speed radio intercept

operator. From there I went to Monterey, California, to the Army

Language School to learn Chinese Mandarin and only then was I sent to

Korea.

My involvement with the

company orphanage committee was intense. Somewhere I noted that

in the first six months I was in Korea I had sent out over 1,000 letters

soliciting help for the orphans. I was spending upwards of 20

hours each week on orphanage affairs, this after pulling my regular

shifts in the operations tent or guard duty. Elsewhere in this

web site you can read my letters to folks back in the 'States about

the children. Suffice it to say the experience had a deep emotional

impact on me.

On returning to the 'States

I enrolled at Monterey Peninsula College in Monterey, California.

There I organized several campaigns to collect material for the orphans

in Korea and was pleased to be able to send upwards of twenty tons of

material aid to the orphanage the company was supporting. After

earning the Associate in Arts I went to the University of California

at Berkeley for the BA and MA in history and sociology, respectively.

I continued my interest in China and, for one semester, was the only

student studying the Tibetan language. Mainly, though, I focused

on comparative social institutions. Three years of high school

teaching followed after which I entered the U.S. Foreign Service.

After training at the Foreign Service Institute in Washington, D.C.

and Arlington, Virginia, I went with my wife and newborn Down syndrome

son David to Colombia.

For several years I served

as the Director of the Centro Colombo-Americano, the USIA cultural center

in the city of Manizales. While there I became very involved in

community organizing. Saturdays and Sundays my wife Mary Ann and

I (with David in a pack on my back) would visit the poor barrios of

the city. After awhile we became familiar figures in the poorest

sectors of the city of almost a quarter of a million inhabitants.

Mary Ann worked two days a week as an R.N. and was one of five registered

nurses in the four hundred-bed university hospital. We donated

her entire salary to the local orphanage of over 200 children.

It comprised over half of their monetary income for the time we were

there. The children went begging "sobreitas" (leftovers)

from house to house to supplement their diet.

I really feel it was

the exposure to the plight of the orphans and the battered civilian

population in Korea that made me sensitive to the problems of survival

of the poorest sector of this city in Colombia. I was not shocked

at what I saw and could communicate with the humblest of the slum dwellers,

treating them with dignity and respect knowing full well that they were

not responsible for their plight. I was able to develop programs

in the national prison, in the slums, in the industrial trade school

for poor boys and in the orphanage. The literacy program we developed

in the US cultural center was one of the largest in the nation.

When we left to return to the US to pursue the Ph.D. (and get David

specialized help) we were named honorary citizens and given the keys

of the city in gold, the first time such was ever given to a foreigner.

We were also given many other awards for our service to the lower social

classes of the city. For me it was a continuation of my work that

began with the orphans in Korea.

The Sociology Department

of the University of Wisconsin at Madison offered me a grant to study

there for the Ph.D. I took the concentration on social organization

and focused on community systems analysis and voluntary action.

(The Korean experience popping up again?) The doctoral minor was

in Latin American Studies. Wanting to go back to the West Coast

I took a position in the Sociology Dept. of Western Washington State

College, now Western Washington University, where I remained until retirement

in 1990. When we moved to Bellingham in 1967 our family included an

adopted racially mixed son named Todd.

The next twenty-two years

had me involved in scores of community action projects at the local,

regional and state level. Most of those involvements were with

social causes addressing problems of poverty, racial discrimination,

social justice and issues relating to mental or developmental disabilities.

In 1974 I became the first Ph.D. teaching faculty at the university

to be elected to the Bellingham City Council in its 74-year history

in the town. On the City Council I continued to be an activist.

The Korean War experience with the orphans taught me the lesson that

the efforts of one person can make a difference and with the coordinated

efforts of many the impact can be remarkable.

At the university I was

named Chair of the Center for East Asian Studies, Special Assistant

to the President for International Programs and finally, until retirement,

served as Director of the Office of International Programs.

In about 1985 Mary Ann

and I decided to open a small "mom, pop and handicapped kid"

nursery to provide employment for mentally retarded, mentally ill and

brain damaged youth, beginning with David. I built a solar greenhouse,

Mary Ann quit nursing and together we cleared the woods near our house

for a nursery specializing in rhododendrons, azaleas and Japanese Maples.

We planted in the woods the plants we were selling so the visitors would

eventually see what a mature plant would look like. The city

park department eventually purchased our land for a city park and we

put the entire amount of the sale in the local community foundation

to be used to support programs for the mentally ill and developmentally

disabled in the park. For a number of years I chaired the city park

department sculpture committee that is developing the park into a major

sculpture garden. It is there that we built the Korean War Children's

Memorial pavilion.

When not in my office working on issues

relating to the Korean War Children's Memorial I am often out on my

bicycle. I ride thousands of miles a year and from time to time

participate in bicycle races. I maintain that the only way I will win

a race is to out-live the competition. Now in my mid-70s I'm doing that

and am bringing home the gold. Even though I am usually the only person

in my age group I still have to ride the course. Darn! People

ask how I can find time for cycling with all my other activities.

I explain that they have it backwards. I can do all the other

things because I keep myself fit on the bike.

This is the shortened

version of "The Story of George F. Drake". Some day I will

write an autobiography but for now I am too busy creating more content

for that story.